FANTASY as A FORCE for CHANGE

As India becomes the world's third largest economy, the battle to define its cultural, social and sexual future is on.

Just as sexual fantasy can be a crucible for personal exploration, sexual liberation can drive change on a national scale: As India becomes a leading economic power with a vast youth population, we asked two leading voices of sexual expression in the country how competing conservative and liberal traditions are vying to shape its new identity.

Fantasy gives us license to explore what the law, social taboos and our self-imposed limitations keep us from in any given time or place. So just as Nancy Friday's My Secret Garden represents a snapshot of American women's forbidden desires in 1973, Want has captured the same for respondents to Gillian's invitation to share in 2024. But that exploration of the illicit can also be the first step to wider changes, as a platform to bring what we learn about ourselves in that private space to bear in the world around us.

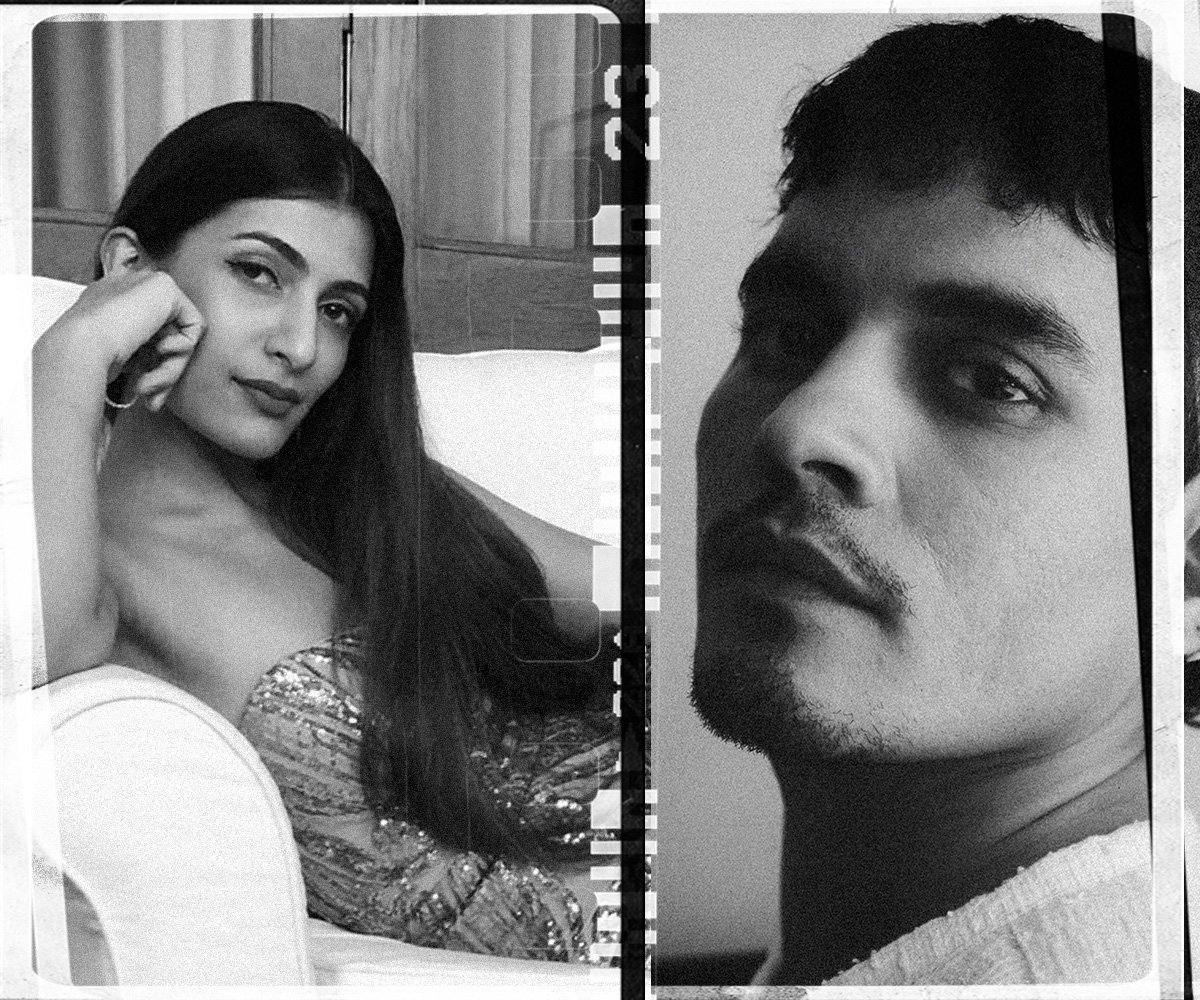

As a study of social change, there is perhaps nowhere on Earth today where competing traditions of conservative patriarchy and sexual liberalism–now enabled by the internet's collective subconscious and amplified by social media–are shaping and reshaping the landscape of public morality quite as rapidly as in India. To understand more about the role of fantasy in all of this, G Ode spoke to two leading voices of sexual expression in the country–sex educator and founder of intimate care brand Leezu's, Leeza Mangaldas; and Creative Director of culture, fashion and art magazine Dirty, Kshitij Kankaria.

To understand where India finds itself today, you have to know a little of its history. Over centuries, the spirit of sexual liberalism that produced the Kama Sutra coexisted in a fluctuating balance with a tradition of arranged marriages and the restrictions of the caste system that prohibited marriage outside of one's own social status. However, under colonialism, the culture's more repressive tendencies found a perfect ally in British puritanism. Even talking about sex–whether in public entertainment, privately between friends, even between partners outside of marriage–became socially forbidden.

"The odds are so stacked against you, especially for women and queer people, that it's hard to be expressive about wanting sexual agency or having a sexual identity." Leeza Mangaldas

While the importance of marriage has declined in the West (and with it, sexual freedom has tended to rise), strong cultural traditions and religious resurgence in India has seen arranged marriage–and therefore strictly no sex before marriage–remain the norm for around 95% of India's young people. Not only is this prohibitive of sexual exploration for the country's vast youth population (over 40% of Indians are under 25), but the age of marriage is on the rise as women begin careers and men need longer to save enough money to be a viable marriage prospect. According to Leeza, as a sex educator, she would increasingly hear that neither women nor men experience their sexual awakening until their mid to late 20s, so both seek out ways to explore their sexuality in private. And in many ways, Leezu's is her response to that, even though censorship laws require her to market her sex toys as 'massagers':

“For women, a lack of pleasure in their sexual experiences was a common refrain. For men, it was a lack of sex: 'Will I ever have sex? Who would want to have sex with me? My parents would never let me have sex and I can't afford to get married' … and I thought 'toys can solve both these problems'.” Leeza Mangaldas

And in a country in which censorship bans sexual content including porn and even explicit scenes in mainstream foreign movies, Leeza found the rise of social media an invaluable tool for reaching people with sex and health-positive messaging despite the prevailing custom of silence.

"The [early days of the] Internet allowed for a collective subconscious to manifest in tangible ways where you could find the people who wanted the same change as you." Leeza Mangaldas

More recently however, she has found the policies of the US-based tech giants that run the platforms to be increasingly restrictive. The responsibility they have for allowing those in developing nations to access information, she feels, is being sacrificed in favor of maintaining neutrality in the culture wars back home:

"The platforms that allowed this to take place … [have become] so sex negative. After the repeal of Roe v Wade, internet censorship got steadily worse. What's super sad is that these platforms have provided a glimmer of a Utopia … It's very sad to have this freedom and diversity and openness that the Internet once provided so rapidly and punitively curtailed." Leeza Mangaldas

This, she says, is effectively doing the work of the domestic censors for them: "The uncles have made their way to the internet. It was an uncle-free space once".

Kshitij has another take on the advent of the internet: Through VPNs and other workarounds, Indians are able to access banned content, leaving a disconnect–especially in rural communities–between what people's minds are opened up to online and what is available to them in real life. This he says, has led to palpable frustration, especially amongst young men. Some have even suggested that this new access to explicit content has contributed to the surge in sexual violence in some Indian villages.

"There are these two fucking parts of Indian society going in two completely different directions … they're two worlds living together and they don't merge or match." Kshitij Kankaria

This is in some contrast to the experience of India's cosmopolitan, college-educated classes, who's access to travel and international perspectives has led to a far greater openness to almost all aspects of sexuality. Even where there is acceptance however, says Kshitij–himself a member of the LGBTQ+ community–there is no overt gay or queer culture as there is in Western cities and no tradition of non-heteronormative relationships for Indians to follow. In terms of both fantasy and practice, this community is India's Generation One.

"Our love language, our sexual language has all been learned from straight people. In India, we have never had an example of gay relationships or gay love or gay sex. So when I travel and meet with my friends around the world, I think 'how are they so different to me?', and I realise they are two generations ahead of us where they have experience of it being normal to be gay." Kshitij Kankaria

And this disconnect isn't just between different parts of Indian culture: Owing to ideas of shame and social properness there can still be a big difference between what people privately do, think or desire, and what they will admit to in public:

"If you are the kind of person who wants to get into a kink like that [the fantasies described in Want], you would take multiple months before you even open up to your sexual partner to talk about it. The conditioning is that … these kinds of sexual, freaky fantasies are not really accepted, even between two partners." Kshitij Kankaria

"Everyone wants pleasure and people want to have joyful, healthy personal lives, and yet we must pretend that we don't partake." Leeza Mangaldas

There are, however, good signs for the sexual freedoms of future generations. Both Kshitij and Leeza agree that, despite the work of censors both at home and abroad (and perhaps because of it), India's sexual imagination is alive and well.

"When something is taboo, it is often erotic as a result of being taboo. When something is forbidden there is a charge to it." Leeza Mangaldas

Kshitij points to the success of the televised short film series Lust Stories and the work of director Konkona Ser Sharma as evidence that everyday fantasies such as powerplay, voyeurism and infidelity retain their power to capture the imaginations of those who harbour desires beyond the bounds of spoken public morality.

"When I asked her [Ser Sharma] how did you come about this [voyeurism storyline in Lust Stories], she said 'You know it's a very very common fantasy to see people having sex' … It was a super-hit short, so I think people really connected with the idea of it." Kshitij Kankaria

Similarly, Leeza has seen the power of the illicit both to create community (having visited India's own small yet resilient BDSM Kink Con) and to drive feverish excitement (in the runaway success of Netflix's Sex Education). Both however, see the advance of women's equality as intertwined with any serious change in the country's sexual (and wider) liberation.

Wherever men are with their sexuality, women have to be in the same place and hold power and it's not just about producing kids. Kshitij Kankaria

As individuals, fantasy has a vital role to play in the push-and-pull of defining our own sexual identity–a core part of figuring out who we are and our place in the world. In India, we see a similar pattern of exploration, pushback and acceptance on a national scale as economic and social shifts see the country growing into a renewed role as a global superpower. As a key driver of the conversation about women's sexual independence, freedom of media and information, and acceptance of international norms of freedom of expression, the sexual desires of the Indian people are likely to play a huge part in deciding the course which that transformation takes.

"There is so much power in making that first step of recognizing that you deserve pleasure, that you can give yourself pleasure, and fantasy intensifies all of that." Leeza Mangaldas

As a space for mental freedom that can become personal physical liberation and potentially translate into social change, individuals' own minds are a space that the outside world can never fully control.

Fantasy, as Leeza says, is resilient.

"You can't stop love, you can't stop desire. you can't stop people wanting more than they're allowed to have … Fantasies are resilient." Leeza Mangaldas

It’s good to share

Join the conversation

Sign up to be first to find out more and become part of our growing community